Why Are My Photos Dark: Exploring the Effects of Exposure

This is a common problem if you’re only just starting to get to grips with photography because exposure can be very hard to get your head around. Whether you’re shooting in program mode, a priority mode or manual, you want to aim to keep your needle in the center of the exposure meter (below). NOTE: This only applies if you’re shooting in good light. When shooting in a darkened area, you may want your photos to reflect this. There are different shooting modes that I will be talking about in this post but, the majority of the time when your photos come out too dark, your camera is either in one of the auto modes, or in manual. When a camera is in an auto mode, it doesn’t have all of the information that you have such as how to meter, and it will have trouble in low light situations. When you’re shooting in manual, you’re in charge of setting the exposure, which can change as you move the camera even slightly; you may find that, at times, you’re not exposing right.

Flash

This is something I hear people complain about a lot, mostly when they’re using a pop-up flash (that’s a rant for another day). The camera isn’t as intelligent as us… either that or it’s just plain lazy. When the pop-up flash fires, it usually dramatically increases the amount of light that enters the camera and the camera will exposure for this, forgetting about the rest of the photo. Have a look at my photo below for example: the camera has exposed for the subject (albeit rather poorly) but the background is too far away to capture enough of the light from the flash. Altogether, the photo is too dark. There is a way of counteracting this: increase your exposure by extending the shutter speed, boosting the ISO, or widening the aperture. The flash will fire and the camera will freeze any motion, record whatever has been captured and the increase in the exposure will continue to capture the background. Check out my photo below for an example, taken at ISO 1600, 1/30 of a second, at f/2.8, with the flash (external) exposure turned down by 1.33ev. There’s not enough ambient light to overexpose the face.

Metering

Metering is truly one of the most important aspects of exposure as it allows you to tell your camera which parts of the photo you think are the most important. Most commonly, when photos come out too dark, your camera is set to Evaluative/Matrix metering when it should be set to Spot or Partial (or vice versa). Take a look at this post on metering modes to fully understand what this means. Generally, for the sake of helping you understand this here, Evaluative/Matrix looks at the whole photo whereas Spot and Partial only look at a certain part of the photo. I have four metering modes on my camera but I only ever use Evaluative or Spot. Here are a couple photos I shot while waiting for the slowest lifts in the world in Washington D.C. last week, both shot in aperture priority. This first photo was shot on evaluative metering mode and, as you can see, it’s taken the light from the whole photo into consideration to decide on which exposure would work best. The trouble with this is that I’m left far too dark in the middle of the photo, while the windows to the side are still too bright. It’s a poor compromise. When I switched to spot mode, the camera knew that I wanted to be subject of the photo and that it should focus the exposure around me. This blew out the exposure of the windows but that doesn’t matter. Not only is the information from the windows unimportant to me but I actually think it looks better to have them blown out like this, providing a nice contrast. As you can see, metering is very important.

Calibration

When I talk about calibration, I’m talking about your camera’s LCD screen and your computer’s screen. Starting with the camera’s screen, it’s very easy to have this set too bright or too dark. When it’s dark out and you’re trying to see your screen better, it’s natural to turn up the brightness or, worse still, have the camera set to full brightness at all times. When you go into your camera’s brightness settings, there will be a scale to help you determine how bright you should set your camera to prevent against taking photos that are darker than you think they are. I personally have this set up to a custom button on my camera so I can change it on the fly. Calibrating monitors for post production is a different kettle of fish altogether. It’s not easy and, to do it properly, it usually requires some external hardware but there are alternatives. I’ve not written about this in much detail before, so here’s a link to a useful wiki I like to show people.

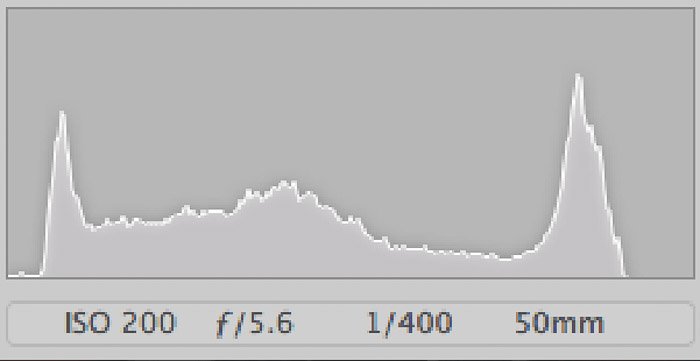

Histogram

As I mentioned above, it’s pretty obvious that your camera’s LCD screen is not the most reliable thing to view your photos on but there are ways to making more use out of it. By using the histogram in your camera, you can see what your camera has recorded, set to a brightness scale. You can read the full article here but, for the sake of this explanation, the left side of the histogram is pure black and the right is pure white. If you have any information in either extreme, your camera has lost information that can’t be recovered. “In a standard jpg image there are 256 different recorded values of brightness; 0 is pure black and 255 is pure white. These 256 values are mapped out in a histogram and each pixel from the image is assigned to a value.” Below is a histogram from a well exposed photo. You can see that the majority of the information stays away from the edges.

They’re not

Sometimes they’re just not. Often, if you’re shooting in low light, you will want your photos to reflect this, especially when you’re shooting at night. If you’re shooting in a dimly lit room, you will want the photos to be brighter than they really are but, sometimes, it’s alright to have some really dark areas because that’s just what the scene looked like when you took the photo.